- Justin Aclin: The Newsletter

- Posts

- The Clock Twink Theory of Art

The Clock Twink Theory of Art

If that title doesn't make you click...

Hi, folks. No publishing news this time. In fact, I wouldn’t expect to hear any for a while. But things are still rolling along in the background, I assure you. (I also assure my 95-year-old grandmother, who when I told her there’s still a bunch of time before my book comes out, said “I hope I’m still here.” No pressure!)

In the meantime, I’ve been thinking a lot about art. It all started with a post I saw on Bluesky, which was about AI. I’m not going to dive into my thoughts on AI in this particular newsletter (I’m ag’in it!), but this thread was quoting someone defending using AI art because, in her words, if you’re not “naturally gifted” at art, learning to make art amounts to putting yourself through “years of hazing.”

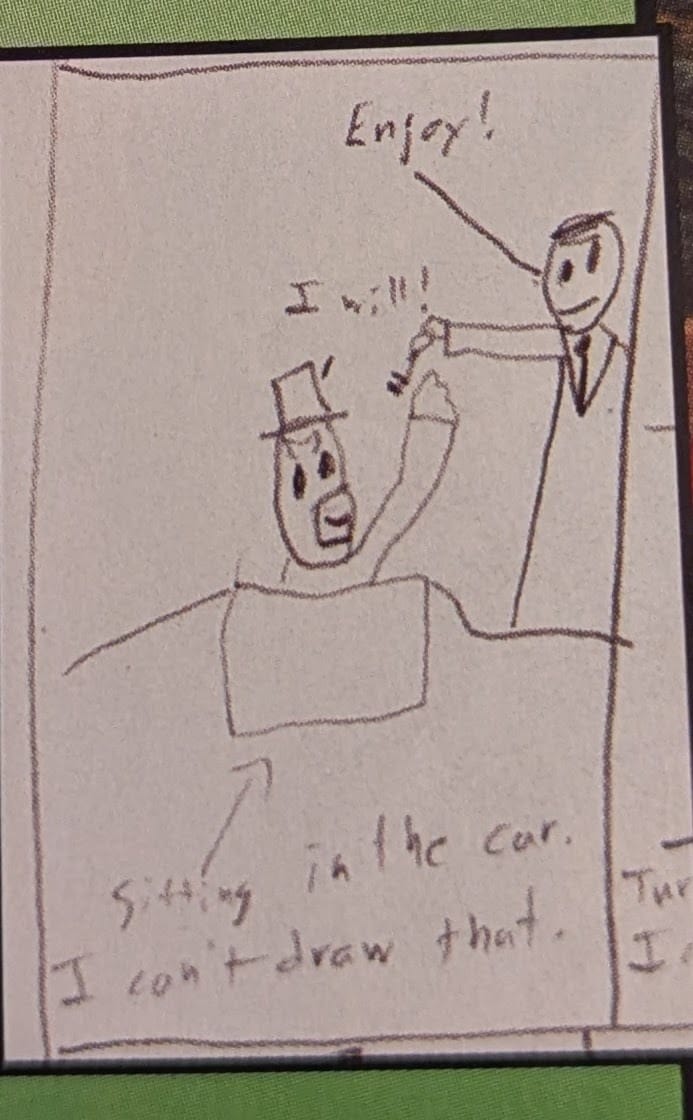

This struck a chord with me, although I don’t agree with it at all. I’ve often wondered if there’s such a thing as natural-born artists. For reference: my father is a professional artist. Also, my brother is a professional artist. By contrast, I’m a professional artist in that I once had a piece of my art published in the second collected edition of Twisted ToyFare Theatre, which was sold in comic book stores. And it looked like this:

I swear to god, this was sold in comic stores.

So, did I just miss the art gene? I don’t think so. As I said in my tweet storm or whatever we’re calling these things these days, I don't believe there's such a thing as a natural artist. However, I do believe that there are some people who are more inclined to be able to put in the hard work to become a talented artist.

Enter…The Clock Twink

Not pictured: the clock

The Clock Twink (real name: Jack) is a character on the HBO program The Gilded Age. He’s a servant to a wealthy family who — although he never studied clock-making — is able to invent a new type of alarm clock that (spoiler alert) makes him a crapton of money.

Clock Twink was not born with an innate ability to invent clocks. What he did have is the type of brain that made him spend innumerable hours (probably — they don’t show it on camera because it would be boring) taking clocks apart, seeing how they work, understanding the mechanisms and figuring out how they can be improved. There were no HBO prestige dramas in those days, so it was probably the most entertaining thing he could do.

Not everyone has the patience to take a clock apart and see what makes it tick! Some people have patience, but don’t take any pleasure in the monotony, or don’t care about clocks in particular. These people, I’m sad to say, will never be Clock Twink.

And presumably this has something to do with art…?

It does, I think!

Learning art takes endless hours of repetition, of trying and failing to capture what's in your brain. I think that there are some people for whom that process is pleasurable, and some people for whom it's kind of torture. For people whose brains work like that, the process of drawing over and over and over again — that is, the process of learning — is enjoyable, and it helps them become artists.

I always say that I draw like a six-year-old (see above), but the truth is when I was young I sat down and really tried to learn to draw. I was copying from art, and I could see what I would have needed to do to get better. But I could also see that it was going to be really hard, and I didn’t think I’d be able to put in that work, or it didn’t feel like the payoff would be rewarding enough for me. Even if you’re not a talented artist, you can still learn to draw. The learning, not the drawing, is what comes easier to some people.

Minutes after finishing my tweet storm, I saw one of my favorite cultural critics, Matt Zoller Seitz, link to a book called “The Work of Art” by Adam Moss, which interviews various creators — from Stephen Sondheim to Roz Chast to Tony Kushner — about the precise work that they put into creating their art. As a well-known process junkie I was intrigued, and I reposted it saying that it seemed really cool, especially related to all the posts I’d just made about natural artists and learning art.

So when I picked it up from my local library, I was only minorly surprised to see a lot of the aspects of my Clock Twink Theory shared by some of the creators in the book. Michael Cunningham, who wrote the Pulitzer-winning “The Hours” (full disclosure: I have not read it) went to school to study art. But, he says, “there were some people in the classes I took who were not only really gifted but who were bottomlessly interested in the fundamental proposition of trying to produce something that was alive. They were indefatigable. …I would get discouraged and give up. The girl next to me would get discouraged and start over again.”

Eventually, Cunningham realized that he could tap into that energy, but in writing, not in art. “I still think it’s really hard to comfortably separate talent from this unquenchable interest in the problem presented by the task. Like, they never got tired of trying to paint. And I started writing and realized that I felt that way about writing.”

It’s how I feel about writing, too, even though I can’t say I never get discouraged and give up. But I view it as an endlessly fascinating puzzle, and when I can figure it out and write something I’m pleased with, there’s almost no better feeling. It’s just like how Clock Twink feels about clocks, except I’m virtually guaranteed never to get rich doing it.

There’s more to it than that, of course. Various other artists in the book point out that you need to cultivate a sense of taste, or you’ll be able to labor endlessly but never know what you’re aiming towards or when something is good or not. And many speak about the balance of being able to knuckle down with being able to walk away, to not force things and let your brain do some of the work for you in the background. (Or the muse, or god..whatever you happen to believe.)

There’s so much that goes into being an artist. It’s not something you must be born with. Ultimately, it comes down to the ability to try and not give up until it’s good enough.

Links to Cool Things

I’m probably only a quarter of the way into The Work of Art but I can already tell it’s going to be a hugely meaningful book to me. If you care at all about creativity, or enjoy seeing the behind-the-scenes notes on a wide variety of creations, I can’t recommend it enough.

Speaking of art, I want to give a special shout-out to loyal newsletter reader (and my long-lost Australian second-cousin — not a joke!) Su Goldfish. She’s an incredible artist in a variety of media, and her documentary film about my family, The Last Goldfish, is the only movie that I appear in, to my knowledge. It’s also deeply moving.

I read Lake Yellowwood Slaughter by Gavin Guidri and my friend Alejandro Arbona, and if you like over-the-top violence, ‘80s slasher flicks and gnarly kills, it’s for you. And they just announced a sequel, Stilletos at Midnight, inspired by Brian DePalma-esque neo-Giallos!

Huge congrats to pal Alex Segura on the announcement of his upcoming horror novel, The Moonlight Children. Alex could easily churn out nothing but mystery novels and have a very healthy career, but he’s out here doing it all!

The new season of King of the Hill on Hulu is surprisingly entertaining! Just take my advice and don’t try to do the math on how old the characters are. That way lies madness (and narrative inconsistency, but it’s okay. I’ve let it go.) Also, like the excellent movie Weapons, Toby Huss is in it. Toby Huss is a delight in everything.

Thanks for reading! And if you happened to find your way here via a web link or something, why not subscribe?